Perception, Reality, and Legacy: An Interview with Bobby Czyz: Introduction To a Three Part Interview

Greg Smith - 9/13/2005

1980 was a pivotal year in boxing history. Larry Holmes scored a one-sided eleventh round technical knockout over Muhammad Ali. Holmes had held the WBC heavyweight title since 1978 with his epic fifteen round decision over Ken Norton, but Holmes didn’t become the true, lineal heavyweight champion until he defeated Ali. It was sad to see the shell of Ali dominated by his former sparring partner, and it was a raw and definitive beginning and end to two of the most significant reigns in heavyweight history.

1980 was also the year Jimmy Carter chose to boycott the Moscow Olympics. Our 1976 Olympic team was probably the best in history, and it’s unfortunate that we didn’t get to see another talent-laden team distinguish themselves against international powerhouses like the Cubans and the Russians. In my opinion, if Carter would’ve chosen not to boycott the 1980 Olympics, the careers of many young men would’ve moved forward quicker and more lucratively in the professional ranks.

1980 was also the year NBC created the concept of “Tomorrow’s Champions.” Several talented former amateur stars had just turned pro, and were showcased on free TV as future champions in the sport. Among the stars being showcased were Tony “El Torito” Ayala Jr., Johnny “Bump City” Bumphus, Davey Moore, Alex Ramos, Tony “TNT” Tucker, and a few other fighters.

Ayala was a junior middleweight terror and the most precocious of the group. Ayala turned pro in 1980 at the age of 17, and had reportedly not lost a fight since the age of 8. At the age of 14 in 1977, he engaged then WBA welterweight champion Jose “Pipino” Cuevas in an infamous sparring session in Ayala’s hometown of San Antonio, Texas. By all accounts, Ayala got the better of Cuevas, and the brutal punching Mexican champion was heard muttering “increible” repeatedly after the session was over.

As we all know, Ayala allotted a professional record of 22-0 (19 KOs) by late 1982, and was on the verge of a title shot with fellow “Tomorrow’s Champion”, WBA junior middleweight champion Davey Moore. Most expected Ayala to unseat Moore and go on to fights with Hearns, Hagler, and Benitez. Instead, Ayala was convicted of rape in early 1983, and served 16 years in the New Jersey penal system. Ayala attempted a comeback upon his release in 1999, but the comeback fizzled out after Ayala broke his hand and was stopped by Luis “Yory Boy” Campas in 2000. Last year, Ayala, who had numerous scrapes with the law after being released, was sentenced to ten years in prison.

Twenty-five years after the implementation of “Tomorrow’s Champions”, I think it’s noteworthy that none of the above fighters became long-term world champions. Bumphus won the WBA junior welterweight title in 1984, but lost his title in his first defense.

Davey Moore won the WBA junior middleweight title in only his ninth pro fight in 1982. He defended his title three times in less than seven months, but was brutally stopped in eight rounds by Roberto Duran at Madison Square Garden in May 1983. Moore briefly rebounded with a surprise stoppage of Wilfred Benitez in 1984, but was never really the same. Moore died in a tragic accident at the age of 28 in 1988 when he slipped on his driveway and was crushed by his car. Alex Ramos never won a world championship. Ramos is actually better known as the founder and chairman of the Retired Boxers’ Foundation. Detroit-based Tony Tucker won the IBF heavyweight title with a tenth round TKO over Buster Douglas in 1987, but lost the title in a unification bout with Mike Tyson that same year.

Ironically, the most well known and most marketed member of “Tomorrow’s Champions” wasn’t initially chosen to be part of that elite group of prospects. Bobby Czyz, the articulate and multi-talented “white, bright, and polite” middleweight prospect and “matinee idol” was actually shunned and excluded by NBC as one of “Tomorrow’s Champions” in 1980. Bobby didn’t become part of the NBC marketing machine until 1981 after he tallied an impressive string of wins that attracted the attention of boxing experts.

Czyz was a decorated amateur. His amateur record was 24-2, and he was chosen to be part of the U.S. amateur team that traveled to Poland in early 1980. In a strange turn of fate, Czyz wouldn’t be with us today, nor would he have had a professional boxing career, if he wouldn’t have suffered a broken nose in a car accident a week before the team was scheduled to depart for Poland. Much to his chagrin at the time, Czyz was unable to travel with the team because of his injury. At it turned out, his injury saved his life. All members of the U.S. amateur team died in the LAT Polish Airlines plane crash en route to the competition.

Czyz turned pro in April 1980 two months after his eighteenth birthday. A stand-up boxer puncher with heavy “shotgun” jab, Czyz was unusually poised for an 18-year-old prospect. Despite being bypassed by NBC, and earning paltry $200 purses early in his career, Bobby put together an impressive nine bout winning streak in his first year as a pro. He dissected and dominated men ten years his senior, and began attracting sell out crowds at Totowa’s Ice World in northern New Jersey. Many forget that Bobby Czyz didn’t start his career as a spoiled prospect with a huge signing bonus. Bobby Czyz actually carved out his reputation through hard work, and earned the attention of fans and the boxing cognoscenti in the form of a hard earned apprenticeship.

The New Jersey native also stunned interviewers with unusual intelligence and gift of articulation. Czyz was an honor student in high school. He graduated sixth in a class of 335. He was nominated for an appointment at West Point, and was accepted to Rutgers, Arizona State, and Seton Hall. As Czyz told reporters early in his career, he was “the antithesis of the stereotypical fighter.” In a cost benefit analysis, Bobby chose boxing as a career because he believed that he could leave a permanent and indelible legacy for himself and his family while making a lot of money in the process.

After NBC realized their error, Bobby’s natural marketability took hold quickly. After defeating tough veteran journeyman Teddy Mann in his eleventh pro fight in February 1981, Bobby became a central figure of “Tomorrow’s Champions” on NBC. Additionally, Bobby played a massive role during the early days of ESPN as well. Suddenly, Bobby was in the national spotlight at the age of 19. Throughout the remainder of 1981, Bobby was on cable and free TV several times in front of adoring fans. One fan traveled all the way from Alaska to see Bobby in action, and named his child after Bobby. Bobby ended the year on a roll with a record of 16-0 (12 KOs).

Just prior to his twentieth birthday in January 1982, Bobby was matched with Marvin Hagler’s half brother, Robbie Sims, in a critical middleweight bout. Sims was 12-0 (8 KOs), and had an amateur record of 89-8. It was a high risk fight for both men. Marvin Hagler was ringside for the bout, and admitted to being nervous before the fight because he knew Bobby presented a major test for his half brother and sparring partner.

In a tough ten round war, Bobby defeated Sims in a unanimous decision. He punctuated the win with a knockdown in the tenth round. Bobby passed a major test while showing guts, skill, and stamina against a fundamentally sound and skilled southpaw. Nielsen ratings went through the roof. Interview requests increased, and his visage appeared more and more on the cover of boxing magazines. Despite Bobby’s age, his poise, charisma, and skill set provided crossover appeal. His fan base continued to grow, and he was beginning to be mentioned by boxing writers as a legitimate contender.

In November 1982, Bobby’s record was 20-0 (15 KOs). He was ranked in the top ten, and it seemed inevitable that he would land a title shot once he matured more and became battle-tested against top contenders.

In a gutsy and controversial management move, Bobby was matched with the rough, granite-chinned, and grizzled number three contender, Mustafa Hamsho. Hamsho was known for his prodigious strength and almost inhuman resilience. He had beaten the tough and powerful Curtis Parker in a controversial ten round brawl, knocked out Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts, and scored a ten round decision win over former champion Alan Minter. Hamsho got his title shot in October 1981. He was butchered by Marvin Hagler on an 11th round TKO. Hamsho took over 50 stitches in defeat, but was openly defiant and never knocked down in defeat.

After losing to Hagler, Hamsho’s colorful manager, Paddy Flood, discussed retirement with the Syrian immigrant. Stubborn and resolute, Mustafa refused, and proceeded to win a clearer ten round decision over Curtis Parker in March 1982. After battering overmatched Gil Rosario in his next fight, Hamsho was looking for another win to solidify his reputation as a viable contender, and Czyz fit the bill.

Hamsho trained in Miami for the bout, and forged himself into optimal condition. The New York-based southpaw appeared tanned, heavily muscled, and confident when he entered the ring. In contrast, Czyz appeared pale and dry in the opposite corner before the first bell. Bobby used a diuretic to make weight days before the fight. Even though Bobby was only 20, he had trouble making the 160 pound limit during his entire middleweight career. In the end, Bobby tried to box Hamsho as a southpaw during much of the bout, broke his right hand in the second round, and lost a clear cut decision to his more experienced opponent.

After losing to Hamsho, Czyz was viciously attacked by the press. He was labeled as a synthetic media creation, a pretender instead of a contender, and not ready for prime time. Unfortunately for Bobby, more adversity was waiting in the wings.

Bobby’s injury in the Hamsho bout required surgery. A bone graft was taken from his hip, and his hand was in a cast for almost three months. The forced inactivity proved to be the least of his problems.

In June 1983, Bobby’s father, Robert Czyz, Sr., committed suicide. Bobby’s relationship with his father was ambivalent and complex. Understandably, the suicide had a massive impact on both Bobby’s family and Bobby’s psyche.

Nevertheless, Bobby resumed his career at 162 pounds less than three months after his father’s suicide with an impressive technical knockout over rugged, but overmatched Bert Lee on the undercard of the Aaron Pryor – Alexis Arguello rematch. To this day, I am still surprised by how explosive and sharp Bobby looked in that bout considering the events of 1983, and the longest layoff of his career at the time.

From 1983 – 1985, Czyz put together an impressive eight bout winning streak. He split with the Duvas, and became self managed. In 1984, the super middleweight division was created, and Bobby seemed to be the perfect poster child for the inception of the division. Bobby’s weight fluctuated between 162 and 174 ½ pounds during that time, and he appeared much more comfortable in that weight range than he did at 160 pounds.

During that period, Bobby fought some of the best bouts of his career, including a fantastic fourth round technical knockout of knockout artist Tim “TNT” Broady. This particular bout ranks number four on my list of the “hidden classic” fights of the last twenty years. It is a study of fundamentally sound execution in a pier six environment. Everyone should have a copy of this fight in their collection.

During that period, Bobby fought some of the best bouts of his career, including a fantastic fourth round technical knockout of knockout artist Tim “TNT” Broady. This particular bout ranks number four on my list of the “hidden classic” fights of the last twenty years. It is a study of fundamentally sound execution in a pier six environment. Everyone should have a copy of this fight in their collection.

Despite Bobby’s success, he was left out of the championship loop at 168 pounds. Strangely, Murray Sutherland became the first super middleweight champion in history in March 1984 with a fifteen round decision over career journeyman Ernie Singletary. Sutherland lost the title in July of that year on an 11th round technical knockout to Chong Pal Park. Czyz should’ve received a title shot at that time, but through various twists and turns, Bobby continued to win, but labored in near obscurity.

Ironically, weighing just over the super middleweight limit, Bobby dominated Murray Sutherland in a ten round unanimous decision in July1985. Bobby never competed in the super middleweight division again. In my opinion, in watching several of Bobby’s fights during that time, 168 was a great weight for him. I think he would’ve beaten Chong Pal Park on an easy decision or stoppage. More importantly, winning a title at that weight would’ve functioned as a catalyst in bringing Bobby back into the national spotlight, would’ve drawn more attention to a newly created weight class, and Bobby’s name and market appeal would’ve translated into some excellent pay days.

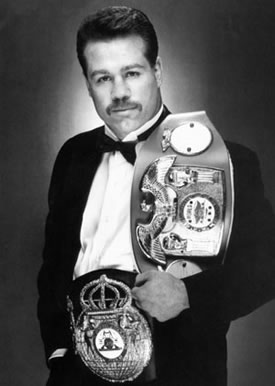

Over a year after defeating Sutherland, Bobby moved to the light heavyweight division and was granted a title shot against IBF light heavyweight champion Slobodan Kacar. Kacar was an Olympic Gold Medalist in the 1980 Moscow Games, and won the IBF title in December 1985 with a 15 round decision over former WBA champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad. Muhammad was past his prime at the time, but was still a name opponent, and had not lost a fight since losing his WBA title to Michael Spinks in 1981. After several postponements, Bobby bombed and stopped Kacar over 5 one-sided rounds to win the title on September 6, 1986. Over five years after becoming one of “Tomorrow’s Champions”, Bobby was finally a real champion.

Bobby successfully defended his portion of the light heavyweight title three times. In his first defense, Bobby destroyed David Sears in 61 seconds on December 26, 1986.

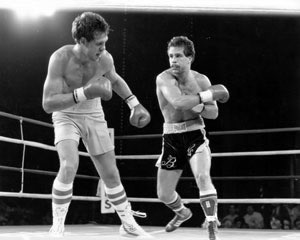

Less than three months later, Bobby faced wicked punching and dangerous Willie Edwards. Edwards had knocked out former champion Matthew Saad Muhammad and future champion Donny LaLonde. He was extremely confident and disrespectful of Bobby in the days leading up to the bout. He claimed that Czyz wouldn’t last four rounds. The normally respectful Czyz was stung by Edwards’ bombast, and Bobby agreed that the bout wouldn’t last four rounds, with the exception that Edwards would be the knockout victim. This set the tone for one of the most vicious donnybrooks in light heavyweight history.

Both men came out of their corners throwing bombs at the opening bell. Czyz landed shocking jabs and overhand rights, while Edwards looked for openings with his sleep inducing right hand. It was obvious that neither fighter was interested in going the 15 round distance. Both men were more interested in putting as much damage on the other in as short a period of time as possible.

Towards the end of the first round, Edwards found the range, and landed a perfect, flush right hand. Bobby went down, but the ropes caught him on his way to the deck. Bobby was catapulted up by the ropes, whereupon he spun Edwards around, and landed a quick right hand counter before the round ended. It was in an incredible round, but the tone was set. Bobby could take Edwards’ best shot, and recuperate quickly.

In the second round, Czyz and Edwards bombed again. After several ferocious exchanges, Bobby hurt Edwards and backed him into a corner. He found the range and unloaded a sweeping right hand that knocked Edwards cold. Referee Rudy Battle counted Edwards out, but he didn’t have to. Edwards was down for several minutes after the knockdown. Bobby proved that he could take a punch from one of the heaviest hitters in the division, rebound, and score a dramatic knockdown.

The critics were starting to take notice.

In his last successful defense in May 1987, Bobby put on a wonderful technical display by insidiously dismantling “Diamond” Jim MacDonald in six rounds. It is one of Bobby’s best performances taken in the context that he was developing the reputation for being a brawler in his knockout wins over Sears and Edwards, but used his boxing skill to defuse a big puncher like MacDonald.

A few months after stopping MacDonald, KO Magazine did a feature cover story on Bobby titled: “Bobby Czyz: Finally, His Accomplishments Match His Appeal.” Indeed, it had been a long, hard road since the Hamsho loss almost five years before, and it was the right moment to recognize Czyz. He had been undefeated for almost five years, and had scored several big wins during that time.

Unfortunately, more adversity was waiting for Bobby again.

Bobby had hoped to unify the division by facing Thomas Hearns in a superfight. Hearns had won the WBC light heavyweight title on a tenth round TKO over Dennis Andries on March 7, 1987. In another example of hard luck in landing the elusive mega-fight and pay day, Hearns went back to the middleweight division, and Bobby had to fulfill his mandatory against Prince Charles Williams.

Less than two months after the KO Magazine article appeared, Bobby lost his title on a ninth round technical knockout to the previously unheralded Williams on the undercard of Hearns – Roldan in Las Vegas. Bobby opened the bout strongly. After brutal exchanges in the first two rounds, Bobby floored Williams with a tremendous right hand at the end of the second round. Williams should’ve been given a mandatory eight count as he struggled to support himself on the ropes after the knockdown as the bell rang, but referee Carlos Padilla ignored the rule.

In the third round, Bobby smartly jumped on Williams again. He caught Williams with another big right hand, Williams helplessly sagged into the ropes, but didn’t go down. Inexplicably, Padilla stepped in and gave Williams an eight count despite the fact that an eight count only applies after a knockdown. This gave Williams extra time to recuperate, and Bobby was denied a chance to follow up. In my opinion, in watching tape of the sequence of the events, Bobby was in perfect position to land a follow up right hand from the blind side while Williams was helpless against the ropes. Considering the fact that Bobby was one of the better finishers in the business at that time, he probably would’ve scored a knockout.

The eight count proved to be a turning point in the fight. Williams showed excellent recuperative powers, and took control of the bout after Bobby appeared to punch himself out. Williams used effective and intelligent double and triple jabs, uppercuts, and right hands to wear Bobby down. Bobby’s right eye swelled hideously in the following rounds, and the bout was stopped in between the ninth and tenth rounds after the swelling grew to grotesque proportions.

Bobby Czyz was back to square one.

In 1988 and 1989, Bobby went into a kind of fallow period. He dropped a decision to former champion Dennis Andries. He won a close split decision over former champion Leslie Stewart. He was outboxed by Virgil Hill in a bid to win the WBA portion of the title. On June 25, 1989 Bobby was stopped in 10 rounds in a rematch with Prince Charles Williams in an attempt to regain the IBF crown. Shortly thereafter, Bobby announced his retirement.

Czyz’s retirement didn’t last long. Boxing was, and will always be, in Bobby’s blood.

In March 1990, Bobby fought as a cruiserweight for the first time, and won a 10 round decision over Uriah Grant. The bout is significant because Grant was a journeyman, but he was a dangerous knockout artist. Of Grant’s 17 wins at the time, 16 were by knockout. Grant hurt Bobby during the fight, but Bobby’s iron chin passed the test against a big puncher, and he won a clear cut decision.

Shortly after Bobby’s comeback win, he was offered a light heavyweight bout with 1988 Olympic Gold Medalist Andrew Maynard. Maynard was 12-0 at the time, and was managed by Sugar Ray Leonard. In an ironic turnabout, Bobby Czyz, once the darling of the media in the early 1980s, was considered a mere steppingstone for Leonard’s prospect. Bobby was a hardened pro with 40 professional fights under his belt, but was considered over-the-hill.

To add to Bobby’s plight, Bobby suffered a pinched nerve in his neck a few weeks before the fight. Nevertheless, Bobby still agreed to take the fight, but under the condition that it would have to be held over the 175 pound limit because he didn’t have enough time to recover from the injury and make the weight.

Weighing 177 to Maynard’s 176, Czyz gradually took charge of the bout in the early rounds, and hurt Maynard on several occasions. Bobby was supposed to be the hunted, but it was obvious that Bobby had become the hunter. Maynard used lateral movement in an attempt to stymie Bobby’s rushes, but Bobby cut off the ring, and landed powerful combinations.

As Bobby began to establish clear dominance, he landed a short, inside left hook that instantly caused Maynard’s right eye to swell. Maynard got on his bicycle, but the end was inevitable.

In the seventh round, Bobby was clearly looking to close the show. After an exchange, Bobby landed a booming right hand on Maynard’s chin, and the Olympian collapsed to the canvas. Maynard took a knee and seemed relatively clear headed, but his will to fight had been sapped. He took referee Frank Capuccino’s ten count, and Bobby exulted in triumph.

It was a huge, poignant win. Bobby had upset the odds, proved the critics wrong again, and forever changed the career of an Olympic Gold Medalist. Maynard was never the same after that loss, and gradually faded into oblivion. It should’ve marked the beginning of a career renaissance for Bobby, but hard luck reared its ugly head again.

After defeating Maynard, Bobby motioned to Sugar Ray Leonard in the ring and briefly discussed a match between the two. In 1988, Leonard stopped Donny LaLonde for the WBC light heavyweight championship and vacant WBC super middleweight title. In 1989, Leonard fought to a controversial draw with Thomas Hearns in their rematch for the WBO and WBC super middleweight title. Especially considering that Czyz had just derailed Sugar Ray’s prospect, a fight with Bobby seemed natural.

Leonard ignored the overtures.

Leonard ignored the overtures.

In the months following his win over Maynard, Czyz was unable to secure a title shot in the light heavyweight division. Additionally, Thomas Hearns had defeated Michael Olajide at 168 pounds less than two months before Bobby’s win over Maynard. Some believed that Hearns – Czyz was a natural match-up, but it never materialized. Bobby was left on the sidelines after his biggest win in years, and was forced to move to the cruiserweight division to get a title shot. Interestingly, Hearns landed a title shot in 1991 against WBA light heavyweight king Virgil Hill, and won a twelve round unanimous decision to win a portion of the light heavyweight crown for the second time.

Bobby won his second world title in a separate weight class with a beautiful boxing display against the bigger and stronger Robert Daniels on March 8, 1991 for the WBA cruiserweight title. Bobby successfully defended his title twice. He decisioned Bash Ali over twelve rounds five months after defeating Daniels. In May 1992, Czyz floored and dominated Donny LaLonde in another twelve round decision. Unification appeared to be a strong possibility. Bobby began doing ringside commentary for Showtime on a part-time basis, and things were looking good. Not surprisingly, Murphy’s Law entered the fray once again.

Bobby never defended his title again. Bobby was hit by a car, and sustained injuries that kept him out of action until 1994. He was forced to relinquish his title, and had to start all over again.

In February 1994, Bobby won a ten round decision over George O’Mara in a non-title bout. Six months later, Bobby challenged heinous punching Nigerian David Izeqwire for the IBO cruiserweight championship. Izeqwire was less experienced than Czyz with a record of 15-0, but the Nigerian had knocked out 13 of his opponents, most of which were naturally bigger and stronger than Czyz. Czyz was doing well in the fight until his back went out. Izeqwire took control, and knocked Bobby down in the fourth round. Bobby was unable to answer the bell for the fifth round. Bobby announced his retirement after the fight.

Once again, the retirement didn’t last long.

Bobby continued color commentary for Showtime, but re-started his boxing career again in March 1995 as a heavyweight. In his heavyweight debut, Czyz scored a fifth round technical knockout over Midwestern journeyman Tim Tomashek. Bobby weighed 206 for the bout, and landed around 70% of his punches. Bobby’s connect percentage stands as a PunchStat record.

More startling is the fact that Tomashek had once given Tommy Morrison problems in a bizarre challenge for Morrison’s WBO heavyweight championship a few months after Morrison won the vacant WBO heavyweight championship in a twelve round decision over George Foreman. Morrison was scheduled to face Mike Williams, but Williams no showed. Tomashek was in the crowd, and volunteered to fight Morrison. Morrison eventually stopped Tomashek in the fourth round, but Tomashek landed some solid blows along the way.

Bobby won another heavyweight bout six months later while weighing 207 ½. On December 5, 1995 Bobby won the third tier WBU super cruiserweight title with a sixth round TKO over previously undefeated Ricky Jackson. The WBU super cruiserweight title was essentially a belt created for small heavyweights in an era of 230-240 behemoths. Bobby weighed 206 for the bout, and knocked Jackson around the ring at will. He dropped Jackson in the sixth, and broke his jaw. I watched the bout live on television, and was startled by how easily Bobby overpowered a naturally bigger man.

In the last two bouts of his career, Bobby was stopped by Evander Holyfield in May 1996, and by Corrie Sanders in June 1998.

Bobby was never off his feet in the Holyfield fight, and absorbed some of Evander’s hardest punches. The bout was stopped after the fifth round when Bobby complained that a foreign substance was burning his eyes and obstructing his vision. Bobby’s trainer, Tommy Parks, was also concerned about Bobby’s often injured back.

Over nine years later, the bout remains very controversial for many reasons. The controversy of this bout was discussed in detail in my interview with Bobby, and readers can deduce the facts when my multi-part interview with Bobby appears shortly.

It is important to note that after stopping Bobby in Madison Square Garden, Holyfield scored one of the biggest upsets in boxing history when he scored an eleventh round TKO over Mike Tyson. Ironically, Bobby was a commentator for Showtime for that historic bout. Bobby will also give his thoughts on Holyfield’s win over Tyson in our interview.

Bobby’s second round technical knockout loss to Sanders convinced him to retire from boxing for good. Bobby packed 247 pounds on to his 5’10” frame in the months prior to the Sanders fight through an incredible weight training regimen and numerous supplements. He slimmed down to 220 by fight time, but was completely overpowered and befuddled by the bigger and faster Sanders. As we all know, Sanders later stopped Wladimir Klitschko in two rounds, and lost to Wladimir’s brother,Vitali, in his next fight.

Bobby’s final ledger reads 44-8 (28 KOs).

Bobby’s final ledger reads 44-8 (28 KOs).

The career of Bobby Czyz is a complex study of multiple contrasts. He was a highly touted and decorated amateur, but was initially ignored by the networks. He fought for very small purses early in his career, and actually made more money selling tickets for one of his fights than he earned in the ring. Once he garnered more attention, the pendulum swung to the diametric opposite side of the spectrum, and he became the most marketed of NBC’s “Tomorrow’s Champions.” When he lost to Hamsho, many experts and casual fans wrote him off as another over-hyped fraud.

Bobby Czyz faced unconscionable personal tragedy in 1983, and later endured a rough and acrimonious break-up with his manager, Lou Duva. He actually fought some of his best fights when he became self managed, but also when many fans were no longer paying attention to him. Nevertheless, through the time honored virtues of hard work, fortitude, patience, and perseverance, he finally won the IBF light heavyweight title six years and almost thirty fights into his professional career.

Throughout his light heavyweight and cruiserweight reigns, Czyz was in the public eye and regained much of his popularity, but he never landed a mega-fight. He also never landed a $1 million pay day.

With roughly the same reach as several lightweight and junior welterweight champions, and often giving away almost a half a foot in height, Czyz eventually tested his mettle against heavyweights. He dominated journeyman competition when he was fighting 30 pounds over his best weight. He put his money where his mouth is against Evander Holyfield. Regardless of the recent controversy surrounding Holyfield’s career, he will be a first ballot Hall of Famer, and is the best heavyweight champion of the last 15 years along with Lennox Lewis.

In boxing history, it is rare for a middleweight to step up and be successful as a light heavyweight. Czyz made the transition, and actually performed better at 175 than he did at 160. Granted, he was a big middleweight to begin with considering his tree trunk, rugby legs and muscular frame. However, as stellar boxing writer Frank Lotierzo can tell you about his own sparring sessions with Dwight Qawi, Michael Spinks, Jerry “The Bull” Martin, Bennie Briscoe, Alex Ramos, and Curtis Parker, taking punches from light heavyweights is completely different than absorbing shots from middleweights. Bobby Czyz never fought the ilk of Bob Foster, Archie Moore, Michael Spinks, or Billy Conn, but he mixed it with the best of his time and did well. He should’ve received another title shot after beating Andrew Maynard. More intriguing is the fact that some believe that Thomas Hearns actually avoided Czyz at 175 pounds because of Czyz’s ability to take a punch and rebound to score knockouts in full tilt brawls.

To take it a step further, Czyz showed true, authentic toughness and chutzpah in taking the risk of stepping up to the cruiserweight and heavyweight divisions. Bobby Czyz became a two-time champion as a cruiserweight, fighting much naturally bigger and stronger men than he did in Mustafa Hamsho, and in his light heavyweight fights as well. Bobby never won a heavyweight title, and none of us expected him to. To be sure, despite not possessing the skill set of an all-time great, Bobby showed unusual pluck in attempting to do what only the most elite former middleweights have done: Go after the best heavyweights of their time.

Bob Fitzsimmons won the heavyweight championship from James J. Corbett in 1897 after holding the middleweight title since 1891. Mickey Walker vacated the middleweight crown in 1931, and went after Schmeling and Sharkey. Greb held the middleweight title from 1923 – 1926, and defeated Walker in a fantastic fifteen round war when Greb was far past his prime. Greb might be the greatest fighter of all-time, and is the only man to defeat Gene Tunney. The Pittsburgher relished in using his speed and unorthodoxy to beat several top heavyweights, and was avoided by Dempsey’s management. Ezzard Charles was once the #1 middleweight contender, never got a title shot as a light heavyweight despite beating Archie Moore three times, and later became the heavyweight champion of the world by dethroning Joe Louis. Past his prime in 1954, Charles gave Rocky Marciano one his toughest fights, and lost a rematch to Marciano later that year.

Archie Moore spent several years in the middleweight ranks before becoming one of our greatest light heavyweight champions. In his 40s, he had Marciano on the deck in a losing effort for the heavyweight championship of the world. Roy Jones won a heavyweight belt against John Ruiz, but Ruiz was considered the weakest of the belt holders at the time. Bobby is not as talented as James Toney, but he is similar to Toney in a sense that he had the guts to after the best heavyweight he could get to sign a contract. As you’ll learn in our interview, Bobby once tried to get Tommy Morrison in the ring, but failed. If Bobby would’ve beaten Corrie Sanders, his plan was to go after Mike Tyson. Bobby Czyz was 5’10” with a 68” reach, but his heart was bigger than most fighters of our era. Whereas most would consider getting in the ring with Tyson during the 1990s as a frightening experience, Bobby actually considered the prospect of fighting Tyson an adrenaline rush.

All told, the story of Bobby Czyz’s career is the antithesis of his persona in the early 1980s. Bobby Czyz outlasted and outperformed all of “Tomorrow’s Champions” through guts and toughness, not slick marketing and smoke and mirrors.

Through the generous help of Matt DiTomasso, I was able to conduct a lengthy interview with Bobby Czyz over the past week. In multiple telephone conversations, we spoke for approximately four hours. We reviewed his childhood, his amateur career, his days as a middleweight contender, and the events surrounding his father’s suicide. Moreover, we discussed the details of his break-up with Lou Duva, the pluses and pitfalls of self management, and what it was like to win the light heavyweight championship after a bumpy and circuitous journey that often teetered on the edge of the abyss. We talked about all of his major light heavyweight fights, his cruiserweight reign, and his crack at the heavyweight division.

Bobby Czyz is unique. More than any other fighter I have ever come across, he is difficult to classify as a person. In addition to his career, we talked about the concept of the soul as it applies to boxing, atheism, the complexity of pugilistic dementia, and his testimony on behalf of Mike Tyson after Tyson bit off a portion of Evander Holyfield’s ear. Other subjects included the difference between organized crime and the sanctioning bodies, the multi-dimensional paradox of his persona, fear, the feasibility of a federal commission to reform boxing, the meaning of his Mensa IQ as it applies to boxing, and his broadcasting career and departure from Showtime. We talked about the fascinating comparisons and contrasts of his sparring sessions with Tony Ayala Jr. and Ray Mercer.

Bobby Czyz is many things. In proper context, he does not possess the chameleon-like quality of a politician or a slick Enron executive. Bobby Czyz is an unusually intelligent person whose character has been forged in unusual circumstances. It’s easy to envision Bobby conducting a flawless PowerPoint presentation to investment bankers at Goldman Sachs, or working as a top flight consultant for McKinsey and Company. It’s also easy to see him going to the opposite side of the spectrum as a fiercely independent entrepreneur in the Silicon Valley during the late 1990s. He operates from a central core code that is unshakable, but also allows him to adapt.

At a different level, it’s equally effortless to see Bobby step out of his business suit, and go at it with the best heavyweights in the world and grin defiantly when he absorbs a numbing left hook and returns fire. I can also see Bobby Czyz as the most fiercely loyal friend a person can ever have, but he can also be the most ruthless and formidable enemy to those who bring out the street side in him. At times during our conversations, he exemplified the “white, bright, and polite” label thrust upon him by the media decades ago. At other times, Bobby kind of reminded me of the Mensa version of Jake LaMotta. George Foreman once called him “tough as nails.” Tex Cobb once called him “double tough.” In a classic 1987 Sports Illustrated Interview with Franz Lidz, Bobby described himself as a “….regular guy. I curse, I make mistakes. I do good. I have a wide spectrum of feelings.”

Over the next few days, Hardcoreboxing.net will present a three part interview with former light heavyweight and cruiserweight champion Bobby Czyz. You will get a fascinating glimpse at one of the most compelling boxing figures of the last 25 years.

Discuss This Now on the NEW HCB Message Board

Send Greg your Questions

Copyright © 2003 - 2006 Hardcore Boxing Privacy Statement

|