Michael Dokes and The Heir Apparent Syndrome

Greg Smith - 4/18/2005

The Heir Apparent Syndrome: A popular and talented contender who never reaches the expected heights of his career.

At the moment, Jermaine Taylor is considered the heir apparent to the middleweight throne. Indeed, Taylor was my 2003 Prospect of the Year, but strangely enough, his career seemed to stall shortly thereafter. Some blame Taylor’s lack of progress after 2003 on Lou DiBella. Informed insiders believe Taylor’s training team should actually accept most of the blame because they reportedly wanted to move him more carefully.

Since that time, one of the knocks against Taylor is that many boxing people---including this writer---don’t believe he’s served a true apprenticeship. In short, if a fighter is the true heir apparent to the throne, the fighter is required to serve some sort of apprenticeship to earn that moniker. The middleweight division has been sparsely talented for several years, but Taylor’s crew seemed to be playing coy when faced with the prospect of fighting a ranked contender. William Joppy was the closest thing to it, but he was truly a spent fighter when matched with Taylor last year. Thus, a certain element of risk is attached to the heir apparent label because we’ve never seen him rapped on the chin by a fighter capable of finishing the job.

If Taylor’s team can officially close the deal for a July title shot against 40-year-old Bernard Hopkins, reports indicate that Taylor will gross approximately $1.8 million. Hopkins’ aggregate earnings for about eight of his title defenses equal that amount. If Taylor loses, Taylor and his team make a lot of money. If Taylor proves his worth and wins, his value skyrockets exponentially. It’s a business. Is Taylor the heir apparent, or does Taylor suffer from The Heir Apparent Syndrome? We’ll see.

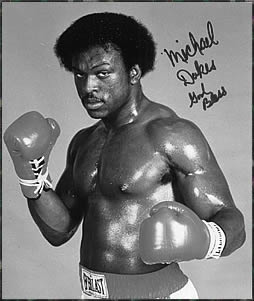

My favorite heir apparent in boxing history is former WBA heavyweight champion Michael Dokes. Unlike Taylor, Dokes served a long and authoritative apprenticeship. Despite a highly decorated amateur career of almost 150 fights, National AAU titles, and a decision loss to Teofilio Stevenson when he was only seventeen years old, Dokes was managed the old fashioned way. He engaged in an exhibition sparring match with Ali. He sparred with Larry Holmes. He fought a series of name fighters and solid journeyman while learning the craft as he gradually ascended the ranks.

Massively gifted with almost preternatural hand and foot speed, a granite chin, and a great body puncher with underrated power, Dokes was considered the heir apparent to Larry Holmes’ lineal crown in the early 1980s. When the smoke cleared, however, Michael Dokes suffered from The Heir Apparent Syndrome. Ironically, despite winning a piece of the heavyweight crown, he never truly maximized both his talent and financial potential.

Michael Dokes was born in Akron, Ohio on August 10, 1958. Now age 46, Dokes sits in a Nevada prison. He should be a retired multi-millionaire living in a mansion and enjoying the sun, nightlife, and beautiful women in either of his two adopted hometowns: Las Vegas and Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Life takes many unexpected twists and turns, and the career and life of Michael Dokes represents a fascinating, circuitous, and tragic journey of paradise lost.

Michael was a pro for six years before he won the WBA crown on a controversial first round stoppage of Mike Weaver in December 1982.

When Dokes won the title, it should’ve marked a watershed moment in heavyweight history. Weaver was accomplished and proven, but hard to market because he was shy and taciturn. In contrast, Dokes had paid his dues, and was infinitely more marketable. He was flamboyant, articulate, and cultured. He often threw roses to the crowd when he entered the ring, always talked about “cultivating” his boxing skills, and was a gourmet chef. He had an eclectic set of interests, and was a lot more fun to be around than Larry Holmes.

Holmes, a top 5 all-time heavyweight on my list, suffered from The Ezzard Charles Syndrome. The public didn’t treat Holmes fairly. Regardless of his enormous accomplishments, the public always seemed to be looking for a fighter who was more accessible and sociable. Michael Dokes seemed to be a good candidate to fit that bill after Holmes stopped Cooney.

Due to the controversy surrounding Dokes’ stoppage of Weaver, an automatic rematch was ordered. Dokes vs. Weaver 2 occurred on May 20, 1983 at the outdoor arena of the Dunes Hotel in Las Vegas. The rematch was on the undercard of Holmes vs. Witherspoon. I was lucky enough to attend the card with my father.

It was a hot day in Vegas, and I believe the card marked a major turning point in heavyweight history, but for precisely the wrong reasons. First, a lot of people felt Witherspoon beat Holmes. I briefly talked to Larry Hazzard after the fight while he was eating a hot dog at the concession stand, and he thought Witherspoon deserved the decision. Holmes had been a champ for five years. He now seemed past his peak and ripe for the taking.

At the same time, Dokes was expected to shine that day. It was his moment to prove he didn’t steal the title from Weaver. Dokes reportedly arrived in Vegas about a month before the fight at a svelte 212 pounds. It appeared to be Carpe Diem for Dokes.

A month later, things changed. A day before the fight, post-workout pictures of Dokes and Weaver appeared in the morning paper. Dokes looked somewhat out of shape. He had a big smile on his face and a slight paunch. Weaver appeared heavier than in their first fight as well, but he was cut to ribbons and in great shape.

Rumors were circulating around Vegas that Dokes “wasn’t hitting the ball as a fighter.” He was allegedly partying instead of training diligently during his stay in Vegas. He weighed in at a rubbery 223. Weaver was almost ten pounds heavier than their first fight at 218 ½, but he looked as good at the weigh-in as he did in the papers.

Regardless of Dokes’ lack of spartan conditioning, the Dokes vs. Weaver rematch was a great fight. Video of the fight doesn’t do justice to the vicious punishment both men absorbed and endured over fifteen brutal rounds in the Las Vegas heat. I was sitting about twenty yards from ringside, and it was one of the best heavyweight wars I’ve seen in the last twenty-five years. Bluntly put, Dokes and Weaver beat the hell out of each other.

Dokes came out fast and tried to put Weaver away early again. Weaver survived the onslaught, fought back effectively, and the fight proceeded to take on multiple ebbs and flows. Weaver, his marbled physique glistening under the sun, slammed home repeated thudding jabs to break Dokes rhythm. Dokes sucked it up, and responded with furious combinations to the head and body. It was a very close fight. I had Weaver slightly ahead at the end of fifteen rounds. Dokes unexpectedly swept several of the final rounds despite his relative lack of conditioning. He bit down on his mouthpiece, dug down, and showed the heart of a champion. The bout was declared a draw. Dokes retained his title, but many throughout the stadium questioned the verdict.

The aftermath of the rematch was anticlimactic regardless of the great action. Needless to say, although the Witherspoon fight marked the beginning of the decline of Larry Holmes, it certainly didn’t mark the beginning of the Michael Dokes era. Critics correctly asserted that the verdict and Dokes’ lack of dominance diminished his claim to the throne. Furthermore, he was an easy target for Weaver’s jab, and Weaver wasn’t known for his jab. After all, if Weaver was able to land repeatedly with the jab, Dokes might prove to be cannon fodder for Holmes’ jab. Dokes would need to make substantial stylistic adjustments to emerge as the true heir apparent to the lineal throne. It never happened.

In September 1983, Dokes lost his title in his next defense to Gerrie Coetzee on a tenth round knockout near his hometown in eastern Ohio. It was an embarrassing loss. Dokes came in lighter this time at 217, and promised a “scintillating” performance. Michael later revealed that he entered the ring that night under the influence of cocaine. His career would never be the same.

Dokes wouldn’t fight again until almost a year after the loss to Coetzee. He engaged in a series of lackluster bouts in 1984 and 1985. From the spring of 1985 until almost Christmas of 1987, Michael Dokes was inactive as a fighter.

During that time, I saw Dokes twice. The first time I saw him was near ringside at the first Holmes vs. Spinks fight in September 1985. He was with an exotic looking woman, but Michael wasn’t matched correctly. He looked awful. He had a big set of glasses on, and the texture and look of his skin appeared almost gray. He seemed to be in a state of dissipation.

I saw Dokes again at the bar of a Las Vegas casino in 1986. He looked better and relatively fit. His arms were huge and muscular. It looked like he was drinking club soda. Moments after I spotted him, an uninhibited woman in her 30s approached Dokes at the bar and playfully squeezed his biceps and tried to engage him in conversation. He obviously didn’t know her, and Dokes briefly talked to her but didn’t pay much attention.

It was during this period of inactivity that Michael Dokes embarked on a journey of acute cocaine addiction and almost died. By his own admission, Dokes dropped from 240 pounds to 190. He admitted buying cocaine by the kilo instead of by the ounce. He was staying awake for six or seven days straight. Dokes, with the help of his saintly manager Marty Cohen (Cohen was independently wealthy and never took money from Dokes’ purses), ultimately entered drug rehab when doctors told him he had two choices: change or die.

Dokes went through rehab, put on weight, and started a comeback. From December 1987 until December 1988, Dokes was inordinately active by contemporary standards. He fought eight times and scored seven knockouts. His weight dropped from the 240s to the low 220s. He won the WBC Continental Americas title. He was making solid, incremental progress.

On the plus side, his physique matured and his power seemed to increase. He used superior experience to gain an edge in some of his comeback fights. Truthfully, Dokes wasn’t a better fighter than he was in the early 1980s. He wasn’t the freakishly quick heavyweight who blew out Ossie Ocasio in the first round of their rematch, nor was he the precocious 22-year-old who nearly decapitated John L. Gardner in 1981. He was an older, slower former champion trying to climb the ladder to become a serious contender again after years of wasting his potential.

The incline was steep. Mike Tyson was ruling the division. Other fighters were ahead of him in the rankings. Dokes and Cohen, perhaps realizing that a big payday for Michael might be elusive, took a risk. The risk resulted in what I believe to be the greatest heavyweight fight of the 1980s: Michael Dokes vs. Evander Holyfield.

Holyfield had vacated the cruiserweight crown in 1988, and joined the big boys in impressive fashion by stopping Quick Tillis and Pinklon Thomas that same year. He was zeroing in on a mega-fight with Tyson, and attempted to add more ex-champions to his resume by signing to fight Dokes. They met at Ceasars Palace in Las Vegas for Dokes’ WBC Continental Americas Heavyweight title on March 11, 1989.

Dokes trained religiously for the fight. He came in at a muscular and powerful looking 225 pounds. Surprisingly, he looked much better physically for this fight than when he weighed in at 223 for the Mike Weaver rematch in 1983. Holyfield came in at a chiseled and primed 208.

ESPN Classic is scheduled to air Dokes vs. Holyfield on Friday, April 22. I will not provide blow-by-bow details of the bout out of courtesy to those who haven’t seen it. Simply watch it, and consider my contention that this was the best heavyweight fight of the 1980s.

Nonetheless, I believe it is noteworthy to add that the handlers of Dokes and Holyfield strongly claimed that both combatants were the top heavyweights in the world along with Tyson after the completion of the bout. Customarily, handlers are responsible for hyping their fighters, but I believe they were correct in their assessment. Michael Dokes, to quote Marty Cohen, “came back from the depths of hell” to perform more than admirably in defeat. It was a long climb from the abyss, and Michael Dokes showed special skill, will, and character in this fight even though he was far past his prime.

As it turned out, Dokes was never a serious contender again for the heavyweight title. He tallied three straight wins after the Holyfield defeat, but was unconscious for more than ten minutes after being bludgeoned by Razor Ruddock's infamous “smash” in early 1990.

A year and a half after the loss to Ruddock, Dokes attempted yet another comeback. He ran off nine straight wins in less than a year against tomato cans, former contenders, and journeyman. He was eventually maneuvered into a title shot against Riddick Bowe. Dokes didn’t deserve the shot, and was stopped in one round on February 6, 1993.

Dokes resurfaced in 1995, and fought five more times until 1997. His average weight for these bouts was 282 pounds, and he lost his last two fights. In his final fight, Dokes suffered a broken jaw and was stopped by Paul Ray Phillips in Erlanger, Kentucky. Dokes dabbled in a wrestling career shortly thereafter, but it didn't last.

In 1998, Dokes drifted back into drug and alcohol problems. He was convicted of a despicable crime, and sentenced to several years in prison.

(Author’s note: For more information on Dokes’ conviction, go to:(http://www.reviewjournal.com/lvrj_home/2000/Jan-25-Tue-2000/news/).

Dokes has reportedly violated prison regulations, and probably won’t get a parole hearing for a few years. As he sits in his Nevada prison cell, it’s hard to tell how the rest of his life will unfold.

In evaluating Dokes’ boxing career, it’s obvious that Dokes wasted his talent. He’s the poster child for woulda, shoulda, coulda: The Heir Apparent Syndrome. It’s the cynical, typical story we’ve come to expect in this sport. Upon second glance, however, attached to this story is an eerie and atypical element of his downfall as well.

For many fighters, fear and insecurity are masked by excessive machismo, lack of training, and drug and alcohol abuse. Additionally, fear manifests itself in the ring in a variety of ways, and contributes to the decline of a fighter. As Cus D’Amato taught, and was wonderfully illustrated by Sylvester Stallone in Rocky V, fear represents both a fighter’s best friend and worst enemy.

Ray Mercer talked openly about this subject prior to his bout with Tommy Morrison. When asked by an interviewer if he experienced fear before a fight,Mercer responded:“Definitely...definitely...Fear is a fighter’s best friend.” He absorbed wicked shots from Morrison early in the fight, kept his composure, and destroyed Morrison a few rounds later. Inversely, Morrison later admitted to being stressed by Mercer’s ability to handle his best power shots, and that contributed to fatigue and the knockout loss. Learning to control fear is an essential element of success in boxing.

Although lack of training and drug and alcohol abuse are indicators of fear and insecurity, I don’t believe fear and insecurity were part of Michael Dokes’ psychological make-up. Likewise, I don’t believe fear played a role in his downfall as a fighter and as a person. Instead, I strongly believe a highly unusual LACK of fear proved to be both Dokes’ biggest strength and unexpected demon.

In watching dozens of Dokes’ interviews and fights over the years, he had a unique, carefree, fearless quality about him. Dokes’ manager once said almost sheepishly: “ He’s fearless. He knows no fear.” People without fear also don’t possess normal limits. In kind, Dokes didn’t seem to place limits on himself. Dokes once joked that if you put him in a room full of women, he wouldn’t let up. In his career, it didn’t matter if he weighed 290 or 212, he was confident of victory. In his drug addiction, purchasing an ounce of cocaine could easily become a kilo. A 24 hour drug binge increased to an unconscionable 168 hour drug binge. Fearlessness, not fear, built Michael Dokes’ life and career, and burned them both to the ground.

Send in any Questions or comments!!

Discuss This Now on the HCB Boxing Board

Copyright © 2003 - 2005 Hardcore Boxing Privacy Statement

|