|

|

Fritzie Zivic: Maligned and Revered Part II

Read Part I

Greg Smith - 1/29/2006

Timpav reported that Armstrong spent some time in the hospital after losing the title, and also convalesced in mineral baths in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Nevertheless, many believed that Armstrong would regain his title. The rematch was scheduled for Madison Square Garden on January 17, 1941. Armstrong wouldn't take a tune-up bout before meeting Zivic again.

In the meantime, Zivic would remain customarily busy in an attempt to sharpen his repertoire for the rematch. Approximately six weeks after defeating Armstrong, Zivic met the raw, but powerful left hooker, Al "Bummy" Davis at Madison Square Garden.

Davis, whose colorful, but abbreviated life is chronicled in the book, Bummy Davis vs. Murder, Inc.: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Mafia and an Ill-Fated Prizefighter, was the younger brother of a racketeer. Streetwise and street tough from New York's Brownsville section of Brooklyn, Davis was an underdog against Zivic, but Bummy's wild nature resulted in one of the most infamous bouts in boxing history.

Before a crowd of over 17,000, Zivic took the lead in the first round and landed both legal and illegal blows in the first few minutes. Towards the end of the round, Zivic, who was known for scoring dozens of first round knockdowns in his career, caught Davis with a powerful straight right that sent Davis to the deck. Davis was hurt badly by the punch, beat the count, and hung on until the end of the round.

In the second round, Davis, incensed by further fouling from Zivic, began to land a succession of blatant low blows. Zivic uncharacteristically looked to the referee for help, but to no avail. After a clinch, Davis, in an uncontrollable rage, kept his aim on Zivic's cup, and the crowd began to boo loudly.

Bummy's actions reportedly became so flagrant that the chairman of the NYSAC signaled to the referee to stop the bout and disqualify Davis. Within seconds of the chairman's directive, the referee stopped the fight, and awarded Zivic the win via DQ. As the bout ended, Davis attempted to go after Zivic again before order was restored.

After the bout, the NYSAC fined Davis and allegedly banned him for life. Newspaper reports indicated that Zivic was certainly rough in the first round, but that Bummy's crazed retaliation was so extreme that the ban wasn't met with much protest. Nat Fleischer, a big Zivic fan, reports:

"Granted that Davis was roughed by Zivic in the first round, that was no reason for Bummy taking matters into his own hands in the second session in which he tried his best to maim his opponent by the foulest kind of fighting that has come to my attention in more than 35 years of association with the sport."

In an interesting twist, Davis was eventually reinstated by the NYSAC. As Timpav tells it, Zivic, accustomed to despicable tactics, actually played a significant role in Bummy's reinstatement by putting in a good word on his behalf.

Eight months later, Zivic would outclass Davis and pound him into submission in a savage tenth round stoppage at the Polo Grounds in New York.

Eleven days after the Davis debacle, Zivic starched overmatched Ronnie Beaudin in two rounds. Zivic would meet reigning lightweight champion Lew Jenkins at Madison Square Garden less than one month after dispatching Beaudin. In a battle where the referee inhibited Zivic from infighting, the bout was declared a draw. Zivic would later dominate a rusty and spent Jenkins in a ten round decision in 1942.

Less than a month after sharpening his tools against Jenkins, Zivic met Armstrong again at Madison Square Garden. As expected, the experts installed Armstrong as an 8-5 favorite, but the highly confident Zivic predicted a knockout in seven rounds.

In 2004, I purchased Bill Cayton's audio CD version of this fight. Initially, I had low expectations, as I prefer to see action instead of hearing about it. Surprisingly, I enjoyed Cayton's excellent presentation, which featured Sam Taub's outstanding blow-by-blow ringside call of the bout.

In 2004, I purchased Bill Cayton's audio CD version of this fight. Initially, I had low expectations, as I prefer to see action instead of hearing about it. Surprisingly, I enjoyed Cayton's excellent presentation, which featured Sam Taub's outstanding blow-by-blow ringside call of the bout.

My only caveat regarding the audio broadcast is in reference to the packaging of the CD. It is noteworthy that the picture on the front of the CD mistakenly shows Armstrong pounding Petey Sarron in their featherweight title bout instead of showing the correct picture of the Armstrong - Zivic rematch.

Zivic, weighing in at his normally wiry 145 ¾, went to work immediately on Armstrong in the first round. Behind quick, snappy jabs to the mouth and nose, Zivic began to cross the right hand, and would then switch up and land short right uppercuts on the crouching, 140½ pound ex-champion.

Armstrong rallied with gusto in the second and third rounds, and landed hard combinations which drew a huge reaction from the overcapacity crowd. Ringwise and unruffled, Zivic began to pick his spots, however, and took control of the fight in the next few rounds.

As the rounds passed, Zivic took complete command and began to route Armstrong with his full arsenal. In the audio broadcast, Taub never reported any foul or dirty tactics between the combatants. Instead, he reports that Zivic landed quick, laser-like shots to Armstrong's head and body. As a result, Armstrong's fragile scar tissue began to come apart.

In the tenth, short, vicious right uppercuts snapped Armstrong's head back continuously on the inside. Impressed by Zivic's craft, the veteran Taub exclaimed, "It's an art to land those kind of blows at close quarters. Short punches that travel maybe four inches." Armstrong attempted to retaliate in desperation, only to be met with Zivic's precision counters as the round ended.

The eleventh round of Zivic - Armstrong 2 is one of the most famous rounds in the history of welterweight title fights. Between the tenth and eleventh rounds, referee Arthur Donovan went to Armstrong's corner and gave the weary and battered ex-champion one more round. Armstrong, nearing complete exhaustion, dramatically stormed out of his corner and bombarded Zivic with wicked combinations.

Zivic was stunned by the rally, and backed off and tried to regroup. Armstrong, his face a bloody mask, continued to pursue Zivic with inexorable fury as the crowd screamed wildly in approval. Towards the end of the round, Armstrong began to fade, and Zivic took control once again.

It was Armstrong's gallant last stand.

Armstrong was allowed out of his corner for the twelfth round, but Zivic jumped on him instantly. More blood began flowing from Armstrong's mouth and facial cuts, and Zivic coldly accelerated his attack sensing that victory was imminent. Zivic aggressively landed a succession of left hooks and right crosses on the helpless Armstrong less than one minute into the round, and Arthur Donovan finally stepped in and halted the slaughter.

Armstrong - Zivic 2 was Zivic's finest hour. Entering the ring as an underdog once again, he dissected and dominated Armstrong with his experience, a stellar jab, stamina, pinpoint power shots, and a killer instinct that left no doubt about his skill level and true worth in the championship ranks

Armstrong announced his retirement after the fight, but like most great champions, the retirement wouldn't last long.

Two months after defeating Armstrong again, Zivic took a brief rest, and began a seven fight series of non-title bouts in less than four months. From March 17 until July 14, all of Zivic's bouts were over the welterweight limit, and took place at varied locales such as Fritzie's hometown of Pittsburgh, Boston, Minneapolis, Philadelphia, and New York.

During this period, Zivic appeared extremely sharp in outclassing Davis in their rematch. He pounded the Davis into submission in a savage tenth round stoppage at the Polo Grounds in New York.

Shortly thereafter, Fritzie dropped a ten round decision to contender Mike Kaplan as well. Fritzie reportedly appeared very ordinary. Zivic may have been able to destroy a great fighter like Armstrong, but his peculiar inconsistency would continue for the remainder of his career.

A great example of this was when Zivic lost his welterweight title to Red Cochrane on July 29, 1941. Only twelve days after defeating Johnny Barbara in Philadelphia, Zivic just couldn't get off against the pedestrian, but determined Cochrane over fifteen rounds at Ruppert Stadium in Newark, New Jersey.

Rumors swirl to this day that the fight was actually fixed, but Zivic was reportedly frustrated during the bout, and blamed himself for his poor performance. His gypsy-like travels and peripatetic nature simply caught up with him.

After losing to Cochrane, Zivic and Carney tried to get Cochrane in the ring again to reclaim the belt, but Cochrane didn't oblige. It wasn't until Cochrane was an ex-champion in 1942 when Zivic exacted revenge in a clear-cut ten round decision.

When Zivic took the title from Armstrong, Sugar Ray Robinson was making his mark. Then a growing lightweight/jr. welterweight, Sugar Ray caught the eye of fans and experts alike, and many were predicting greatness for the twenty-year-old stylist. Robinson was also a friend of Armstrong's, and vowed revenge if he was ever able to get Zivic in the ring.

Robinson was granted his wish to face Zivic. Six weeks after Zivic avenged his 1939 knockout loss to Milt Aron with a fifth round knockout on September 15, 1941 at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Robinson and Zivic met for the first time on Halloween Day at Madison Square Garden.

Many friends and advisors of Robinson urged him not to face Zivic. They believed it was too early for Robinson to face a dangerous and experienced opponent who might mete out intractable damage in either victory or defeat. Robinson persisted, and what resulted was an extremely competitive and sometimes perilous bout for the 139 1/4 pound contender from Harlem.

Timpav describes the action of Robinson - Zivic 1:

Timpav describes the action of Robinson - Zivic 1:

"Ray was too fast for Zivic, who tried to get his opponent in close quarters. A snappy left gave Sugar the edge in the first five rounds. Ray accidentally thumbed Fritzie's eye in the 5th, but apologized and Zivic acknowledged the sportsmanlike gesture. Robinson staggered Zivic with a hard right in the fifth, and Zivic did the same with several jolts to Robbie's chin in the 6th."

"In the 7th, Zivic tagged Sugar's chin with a right smash, and almost floored him. But Sugar hung on and came back in good style to finish strong in the last three rounds."

The decision was unanimous for Robinson, and Zivic didn't dispute the verdict. He said Robinson was just too fast for him, and added that he was a strong puncher. Neither fighter was reportedly marked up badly, and both wanted a rematch.

Initially, Robinson was supposed to meet Cochrane for the title after defeating Zivic, but Red had to pull out because of a nagging eye injury he suffered when he took the title from Fritzie during the summer of 1941.

Sharpened by three solid interim bouts, Zivic felt he was better prepared for the Robinson rematch. He entered the ring as a 5-2 underdog in their Madison Square Garden rematch on January 16, 1942.

Zivic was indeed better prepared and determined to reverse the result of their first bout, but Robinson was a more seasoned professional this time. Sugar Ray boxed expertly, and controlled the flow and tempo of the bout more impressively than in their first encounter. Similar to the first fight, however, in the seventh round Zivic was able to land a thudding right hand to Robinson's head, and briefly had him in trouble.

In the eighth and ninth rounds, Robinson and Zivic traded power shots on equal terms, and Zivic was trying to bust open a Robinson cut he opened early in the fight. As Zivic began to mount a rally in the ninth, Robinson suddenly nailed Zivic with a flush combination. The normally titanium chinned Zivic went down face first and rolled to a sitting position. Summoning resolve and using his wealth of experience, Zivic beat the count, and found a way to survive the round.

Robinson would not be denied. Ray unloaded his full arsenal on Zivic in the tenth, and zapped Zivic's nervous system. Seeing Zivic's plight, referee Arthur Donovan stepped and saved Zivic from further abuse as Zivic was on the brink of going down again. It was only Zivic's third stoppage loss in 148 pro outings. Later in life, Zivic proclaimed Robinson the classiest fighter he ever faced.

Robinson learned an enormous amount in his two fights with Zivic. Even though Robinson didn't appreciate Zivic's habit for fouling, he developed a healthy respect for his boxing ability. After Robinson stopped Jake LaMotta nine years later in the famous St. Valentine's Day Massacre, he paid Zivic an enormous compliment. When asked if his final bout with LaMotta was his toughest fight, Robinson replied, "Naw. My toughest fight was with Fritzie Zivic. But this was a tough one all right."

After losing to Robinson twice, most experts felt Zivic was officially moving into the twilight of his career. A good, solid practitioner for sure, but never a legitimate title threat.

As usual, Fritzie pushed on. He won some fights, and dropped some decisions, but never caved in to the predictions of the experts.

As mentioned previously, he easily defeated Lew Jenkins in 1942, and also avenged his loss to Red Cochrane. All in all, he was winning a lot more than he was losing, and it seemed like a good time for another road trip. Nine years after his formative, character building trip to the West Coast, Fritzie headed out to California during the fall of 1942 with the goal of racking up several fights.

In his first bout in his return to California, Zivic engaged in his third and final fight with a comebacking Henry Armstrong on October 26 in San Francisco. No title was at stake, and it was a fast-paced fight pitting Armstrong's persistent body attack against Fritzie's head shots. At the end of ten rounds, Armstrong was awarded the decision, and many ringsiders agreed.

In his first bout in his return to California, Zivic engaged in his third and final fight with a comebacking Henry Armstrong on October 26 in San Francisco. No title was at stake, and it was a fast-paced fight pitting Armstrong's persistent body attack against Fritzie's head shots. At the end of ten rounds, Armstrong was awarded the decision, and many ringsiders agreed.

In protest, Zivic and Luke Carney strongly felt they were robbed. As in their previous bouts, Armstrong was busted up badly by Fritzie's head shots. By comparison, Zivic was relatively fresh and unmarked. Thus, Zivic and Carney felt they should've been awarded the decision.

Three weeks after the Armstrong loss, Zivic lost another decision in San Francisco to Richard Rangel. Zivic felt jinxed, and Zivic and Carney abruptly left the West Coast and headed home.

Zivic ended 1942 with a ten round decision over Carmen Notch in Pittsburgh, and fixed his gaze on a successful 1943 regardless of continued criticism from the boxing press.

1943 turned out to be one of the most productive years of Zivic's career. Zivic fought thirteen times that year. In February and March, he dropped two close and spirited decisions to the great Beau Jack at Madison Square Garden. Jack later said that Zivic was one of the best fighters he ever faced, and taught him valuable lessons in their two fights. Zivic listed Jack above Robinson as the fastest fighter he ever faced.

After dropping closed decisions to Jack, Fritzie followed up with a knockout of Johnny Roszina in Milwaukee in April.

Zivic then met Jake LaMotta for the first time on June 10 in Pittsburgh. LaMotta wasn't yet twenty-two-years-old at the time of their first match. LaMotta and Zivic engaged in four bouts within a period of six months, and it was a heated and controversial series. Although Zivic was past his prime, he hadn't lost a fight in Pittsburgh since his last loss to Charley Burley in 1939.

Determined to restore his status as a viable contender, the 151 ½ pound Zivic pulled out all of the stops against the 155 ½ pound LaMotta. Most ringsiders believed Zivic took a fairly comfortable decision over the less experienced New Yorker. Surprisingly, LaMotta was awarded a split decision. The decision was so unpopular that the crowed reportedly booed for more than twenty minutes after LaMotta's hand was raised.

Naturally, a rematch was ordered, and Zivic and LaMotta met for the second time in a little over a month at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh on July 12, 1943.

The rematch was scheduled for fifteen rounds, and new judges were ordered to alleviate the controversy of the scoring. Zivic - LaMotta 2 was a brutal, arduous battle matching Zivic's savvy against LaMotta's strength and aggression. The 157 ½ pound LaMotta had a six pound weight pull over Zivic this time. Jake landed hard and regularly early in the contest. Despite dropping some of the early rounds, Zivic was able to rally under fire, and opened a cut over LaMotta's left eye. As a result, for much of the battle LaMotta's face was a bloody mask.

Zivic used his edge in speed and experience to regain control in the middle rounds. Fritzie appeared to be ahead in the fight after the tenth round, and some assumed that his experience in the late rounds would earn him a decision this time around.

Unexepectedly, the younger LaMotta actually stepped up the pace thereafter, and many felt he swept rounds 11-15. Both fighters traded salvos of hard blows as the fight ended, and Zivic was awarded a close, controversial split decision. Newspaper reporters were also split in their judgment.

Zivic and LaMotta fought for the third time in November 1943. Partially due to the controversy surrounding their first two fights in Pittsburgh, the ten round rubber match occurred at Madison Square Garden. The Bronx Bull weighed in at 161, and Zivic came in at 149 ¼. Timpav reported that LaMotta was a 3-1 favorite. Zivic was also granted a request to use five ounce gloves. Zivic felt he could cut LaMotta up, and believed using the smaller gloves would increase his chances.

Similar to their second fight, Zivic - LaMotta 3 was a slugfest. Fritzie controlled the first half of the bout, and LaMotta took the final rounds convincingly. Both men suffered cuts, and both went at each other full tilt in the final round. Once again, the decision was split, and LaMotta came out on top. The New York fans actually booed and protested the decision. Zivic, highly popular in New York City even though he wasn't the hometown fighter, gave the fans what they wanted, and most felt he should've prevailed on the cards.

The fourth and final Zivic - LaMotta fight was held at the Olympia Stadium in Detroit, and was scheduled for ten rounds. Like the previous bouts, both men set a fast pace and traded with unbridled aggression. Zivic broke his right hand in the second round after landing a stunning right cross, and LaMotta was able to use Zivic's handicap to his advantage. Zivic was gallant, but was in trouble late in the fight. LaMotta gained a clear unanimous decision. Zivic later stated that LaMotta was the strongest physical fighter he ever faced.

The fourth and final Zivic - LaMotta fight was held at the Olympia Stadium in Detroit, and was scheduled for ten rounds. Like the previous bouts, both men set a fast pace and traded with unbridled aggression. Zivic broke his right hand in the second round after landing a stunning right cross, and LaMotta was able to use Zivic's handicap to his advantage. Zivic was gallant, but was in trouble late in the fight. LaMotta gained a clear unanimous decision. Zivic later stated that LaMotta was the strongest physical fighter he ever faced.

After their fourth and final fight, like Robinson, LaMotta showed great respect for Zivic's abilities. "He's the smartest fighter I ever met. He'll still be good when he's 50."

Zivic engaged in over fifty more bouts after his last loss to LaMotta before retiring from the ring in 1949. Even though he was no longer a title threat, Fritzie drew large crowds and had a few notable wins as the curtain closed on one of the most unusual and active careers in ring history.

In one of the last fights, Zivic suffered the fourth stoppage loss of his career, against Kid Azteca in Mexico City on February 15, 1947. Zivic had defeated Azteca three times in previous bouts dating back to 1939.

Zivic ended his career with two decision wins over Al Reid and Eddie Steele in Georgia during January 1949. The wins occurred just five days apart.

Fritzie's final record is listed as 158-65-9 (80 kayos) 1 NC. After his career was over, Fritzie told interviewers that he actually fought around 300 professional fights. It wouldn't be surprising if Fritzie's claim was accurate. His penchant for fighting on short notice in various locations lends credence to the notion that his documented record is incomplete.

During the final years of Zivic's career, Fritzie functioned as self-defense instructor in the Army during World War II, and engaged in a variety of entrepreneurial endeavors. He bought Hickey Park in Pittsburgh (later to become Zivic Arena), and spent almost $100,000 renovating the doomed facility. He was the master of ceremonies at several nightclubs, tried his hand at selling insurance, and managed a large stable of fighters. Notwithstanding the fact that fighters of the ilk of Robinson, Jack, and LaMotta paid homage to Fritzie's advanced ring intelligence, he wasn't a successful trainer and manager. Some of his prospects showed promise, but none ever reached the heights of the business.

In my opinion, Zivic's career is best described as that of a talented boxer who served a long apprenticeship, was once relegated to journeyman status, and was maneuvered into a title shot through excellent management. When he got his title shot, he shined, and despite being known for being one of the dirtiest fighters in history, he eventually became one of the most popular and respected fighters of his time. The level of opposition Zivic faced is stunning. In retrospect, of his Hall of Fame opponents, only two were able to truly master a clear and focused Zivic: Charley Burley and Sugar Ray Robinson.

After retiring from the ring, Fritzie opened a boxing school in Pittsburgh, and made it a point not to teach youngsters the fine art of fouling. Realistically, Fritzie was truly old school, and sometimes his lack of patience caused him to crack a few jokes about the new generation of kids. One of his famous quotes was: "My God, kids today think that the laces are for tying up the gloves!"

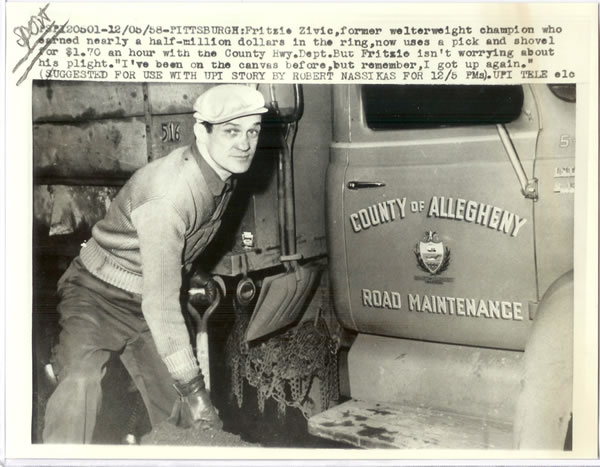

Throughout his life, Zivic wasn't a good businessman, and he lost of a lot of his money in aborted ventures. According to the Lawrenceville Historical Society, he also tried his hand as a promoter, sold wine and whiskey, worked in a steel mill, and later settled in as a boilermaker.

Zivic's marriage to his beautiful wife, Helen, in the early 1930s lasted a lifetime, and Zivic took great pride in his family. Zivic purchased a home in the posh Pittsburgh suburb of Mt. Lebanon, and all of his children became college graduates. Eventually, Helen wanted a smaller home, and they moved not too far away in the same suburb. Later, the Zivic's moved to a Pittsburgh apartment. Some of Zivic's relatives now live in the upscale Pittsburgh suburb of Fox Chapel, the same suburb where John Kerry and Teresa Heinz Kerry own a home.

As mentioned in Part 1 of this article, Zivic was known for his good nature outside of the ring. Even when financial difficulties loomed, he was resolute, and always faced difficulties with grace and humor. He remained popular in Pittsburgh for decades, and died of Alzheimer's Disease shortly after his seventy-first birthday on May 16, 1984.

In Timpav's book, I strongly believe that Zivic's son, Chuck, precisely captures the essence of Fritzie in a eulogy that was printed in the Pittsburgh Press:

"A great deal of Pittsburgh died yesterday when Fritzie Zivic succumbed to Alzheimer's Disease.

But, though they will bury the body of Fritzie Zivic, they never will be able to bury the spirit of the man.

For anyone who remembers the man in the ring, Fritzie Zivic always will be the darting, jabbing welterweight champion. For those unfortunates who never saw him fight but knew him as an after-dinner speaker, he forever will be the rakish, self-deprecating master of humor.

He was a man for his own time, a fighter who could brawl when the situation called for it. He was a champion when Pittsburgh was the City of Ring Champions in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Fritzie Zivic was a man who cherished his Pittsburgh roots and, though his name was a household word in many big cities when he was at the top, he chose to remain in Pittsburgh.

He chose to stay here because Pittsburgh was his kind of town.

But the reverse is also true.

Fritzie was Pittsburgh's kind of man."

Discuss This Now on the NEW HCB Message Board

Send Greg your Questions

Copyright © 2003 - 2006 Hardcore Boxing Privacy Statement

|